Homework assignments with computer games

During my ongoing literature review I often discover interesting facts about things I’ve never thought about. Sometimes I can connect these facts with my own observations: The result is mostly a completely new idea why things are as they are. Maybe these ideas are new to you, too. Therefore I’ll share my new science based knowledge with you!

This week: This time, I demonstrate the idea to use computer games as an additional simulation tool to enhance the learning outcome. Simulation games can be used to validate and visualize the freshly gained knowledge.

I’ve discussed already several times how game mechanics challenge different abilities of the players and thus the players are training these abilities while they’re progressing through the game. I also discussed games like Kerbal Space Program (KSP)[1], because these games simulate real physics and the player can greatly benefit from additional specific knowledge. KSP can encourage its players to learn more about space travel to improve their own gameplay[2].

However, today I like to take a different approach and demonstrate how these simulation games can be also used to enhance the learning outcome. The demonstration will show, that a learner of astrophysics might take advantage of KSP to observe and explore important facts of orbital mechanics.

Typically, a learner does some homework assignments to train the freshly gained knowledge, but often the result can’t be directly verified. Of course, in case of astrophysics it might be possible to validate the results with real world facts. Unfortunately, this can be still very abstract to the learner. However, by using KSP to calculate and simulate orbital mechanics, the learner has the opportunity to simulate the situation and compare it with the own results.

I like to demonstrate this approach with one of my space stations I’ve build in KSP. This space station orbits in an altitude of ![]() around Kerbin (

around Kerbin (![]() ,

, ![]() ).

).

At first, we want to calculate the period ![]() of my space station’s orbit around Kerbin:

of my space station’s orbit around Kerbin:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ P = 2 \pi \left ( \frac {R^3} {G M_\text{total}} \right )^\frac{1}{2} \]](http://blog.learning-by-gaming.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8ee1c89aea70cc46022714a2a80d86ad_l3.png)

We can neglect the mass of the space station in ![]() because the station has almost no mass compared to the planet. So we can just insert

because the station has almost no mass compared to the planet. So we can just insert ![]() as the total mass. We assume that the real world gravitational constant

as the total mass. We assume that the real world gravitational constant ![]() can be applied on KSP, too.

can be applied on KSP, too.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ P = 2 \pi \left ( \frac {(600 e^3 m + 300 e^3 m)^3} {6,673 e^{-11} m^3 s^{-2} kg^{-1} * 5,292 e^{22} kg} \right )^\frac{1}{2} = 2854,783 s \]](http://blog.learning-by-gaming.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-83b1eda6b7d8ae8907d61af2874c74c9_l3.png)

![]()

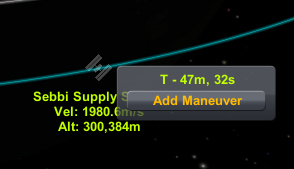

After we calculated the period, we can observe the period in KSP for my station: it does one orbit around Kerbin in 47 min and 32 s. Great!

Now we want to calculate the velocity ![]() of my space station:

of my space station:

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ v = \left ( \frac {6,673 e^{-11} m^3 s^{-2} kg^{-1} * 5,292 e^{22} kg} {(600 e^3 m + 300 e^3 m)} \right )^{\frac {1}{2}} = 1980,839 \frac{m}{s} \]](http://blog.learning-by-gaming.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ead9aab9cf750f52e89921484116bebc_l3.png)

After we calculated the velocity, we can observe the velocity in KSP for my station: it has a current velocity of 1980 m/s. Great!

Finally we want to know the velocity ![]() we need to escape Kerbin:

we need to escape Kerbin:

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ v = \left ( \frac {2 * 6,673 e^{-11} m^3 s^{-2} kg^{-1} * 5,292 e^{22} kg} {(600 e^3 m + 300 e^3 m)} \right )^{\frac {1}{2}} = 2801,33 \frac{m}{s} \]](http://blog.learning-by-gaming.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7b220cdc3d512b0a7de86136f33acb14_l3.png)

![]()

After we calculated the velocity, we can try to plan a maneuver to escape Kerbin in KSP with my station: this time, we’re pretty close to the KSP maneuver, which only requires a velocity change of 806 m/s.

This short demonstration has shown, that a computer game can be used as an enhancement for a traditional learning approach. At first, the learner can take advantage of the specific knowledge about orbital mechanics to calculate some variables. Afterwards, the learner can simulate the calculated variable and validate the own calculation approach. Moreover, the learner can start to manipulate the simulation and learn even more about the connections of different variables and constants of the equations being used.